Biocultural Heritage: The Foundation of a Sustainable Economy

by Claudia Múnera

Porta Palazzo in the city of Turin, Italy, is recognized as the largest open air market in Europe. Visiting this market provides a unique experience: vendors in all directions offer a seemingly endless supply of breads, pastas, meats, poultry, fish, vegetables, herbs, and olives. The kaleidoscope of colors and jumble of aromas threaten to overload the senses. Italians and foreigners alike gather here to find the foods they want – whether it’s a local ingredient for a traditional Italian dish or something exotic to summon the tastes of a faraway home.

Porta Palazzo in the city of Turin, Italy, is recognized as the largest open air market in Europe. Visiting this market provides a unique experience: vendors in all directions offer a seemingly endless supply of breads, pastas, meats, poultry, fish, vegetables, herbs, and olives. The kaleidoscope of colors and jumble of aromas threaten to overload the senses. Italians and foreigners alike gather here to find the foods they want – whether it’s a local ingredient for a traditional Italian dish or something exotic to summon the tastes of a faraway home.

Even though there’s such diversity, all the foods at Porta Palazzo share something in common. You can trace each type of food to a particular ecosystem and a particular way of life for the people who inhabit (or once inhabited) that ecosystem. Each food product in the market comes with its own biocultural heritage. Among all the products we buy and sell in today’s economy, food is probably the easiest to connect to biocultural heritage (assuming we’re not talking about a pre-packaged, frozen microwave dinner). For instance Colombians crave bocadillo veleños, the traditional confection made from guava and sugarcane. And Salvadorians keep an eye out for pupusas, which are made from a cornmeal dough that redefines the phrase “comfort food.” When living abroad, people from a given region often organize festivals in which traditional foods play a central role.

Biocultural heritage wraps a lot of concepts into one term. It’s about relationships between people and the natural environment. It consists of biological resources, from genes to landscapes. But biological heritage also consists of human history, from practices to pools of knowledge and the way humans shape their surroundings and vice versa. According to the International Institute for Environment and Development, some 370 million indigenous people in the world depend directly on natural resources — they rely on their biocultural heritage for survival. Biocultural heritage also influences religious beliefs, sense of place (especially sacred places), and sense of self. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by the tangle of connections when considering the biocultural heritage of a good or a service — maybe that’s why food is a good place to start when trying to get a feel for it. But an astute observer can recognize that other goods and services, such as medicinal plants, tourism, or even health services, also flow from a rich biocultural heritage.

Colorful vegetables, colorful meats, and even more colorful characters make up the scene at Porta Palazza (photo credit: Claudia Munera).

Throughout my career, it has become increasingly clear that conservation of biocultural heritage is the long-term key to maintaining both healthy ecosystems and healthy economies. As a conservation biologist, I could probably be accused of having a biased viewpoint — I have always believed that endangered species, tracts of wilderness, and other aspects of biodiversity are intrinsically valuable and worthy of conservation. As a result, I have spent a lot of time and effort on projects aimed at protecting ecosystems and the species they contain. I believe that maintaining parks and protected areas is a worthy endeavor, but it’s not enough. Drawing boundaries around biodiversity hotspots or cherished scenic areas will fail in the face of ongoing exponential economic growth and mounting pressure to turn protected areas into commodities.

My research on biocultural heritage at the Rio San Juan Biosphere Reserve in southeastern Nicaragua aims to illustrate the point. Nicaragua is changing at a fast pace, trying to follow a European or North American model of economic growth at the expense of its rich natural capital. Deforestation is on the rise with forest cover diminishing from 42,340 square kilometers in 1994 to 30,440 in 2011. There are several causes, but the main one is to meet the demands of markets: cattle for dairy and meat, hardwood lumber, and crops such as palm oil, sugarcane, and peanuts. In short, forests are being transformed into commodity landscapes.

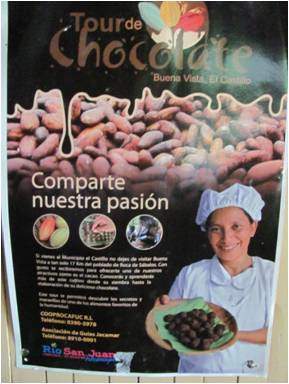

Biocultural services: chocolate tours in Rio San Juan Biosphere Reserve (photo credit: Claudia Munera).

The intense pressure applied by economic growth is threatening flagship species such as the jaguar and tapir, internationally significant wetlands, and the species-rich (not to mention carbon-sequestering) forests of this region in Nicaragua. In light of such pressure, the best way to conserve the natural areas is to recognize the value of the biocultural heritage of these areas. Local communities and indigenous populations are making a living and thriving by growing traditional crops, creating handcrafts, and preparing traditional foods that are founded on the local environment and framed in Nicaraguan history and culture. Several communities are embracing ecotourism (it’s a lot easier to entice a tourist to visit the Rio San Juan, Bosawas, or Ometepe Biosphere Reserves if they haven’t been converted to palm oil plantations or cattle farms). Farmers are also having a go at organic cocoa production. A certain amount and certain types of economic activity are compatible with the natural resources of the region, but if we fail to conserve the biocultural heritage of the region, the natural resources will eventually become commodities in economic activities that are incompatible with the landscape.

Other places around the world also demonstrate how championing biocultural heritage can produce desirable results for people and ecosystems. For example, the provinces of Guangxi and Yunnan, China, contain rice terraces, mountain agriculture, and forests that have provided people with livelihoods for centuries. During the last three years, however, droughts have threatened the economy and local food security. Farmers have relied on their biocultural heritage to cope — planting traditional drought-resistant maize varieties and raising ducks in the rice fields as a pest control strategy. Farmers have accrued health benefits by eliminating pesticides and earned profits by selling their products in niche organic markets.

In Tuscany, Italy, the landscape has been shaped and preserved by centuries of human influence, but in recent times, the people have been engineering the landscape into a homogenized agricultural landscape of mechanized monocultures with no consideration of traditional farming and forestry practices. Consequences include biodiversity loss, erosion, and deteriorating quality of life for residents who have strong ties to their landscape. According to UNESCO, “Cultural landscapes originated by human action, as well as biodiversity connected to them, can only be maintained by preserving local cultural heritage. Abandonment of traditional practices can lead to reduction of landscape diversity with impacts on biodiversity, economy, and quality of life of rural communities. To overcome these problems, parts of the landscape have been included in the World Heritage Sites list (Medici Villas and Gardens). At the same time, ecological restoration of agricultural and natural areas has spurred tourism, revitalized local foods production, and led to the creation of markets for locally grown food that help preserve Tuscan culture.

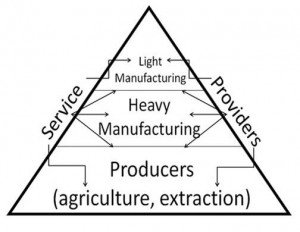

Protecting the biosphere comes down to making sure enough ecosystems around the globe maintain their structures and functions. A strong appreciation of biocultural heritage is a key to doing this job, especially in the face of pressures from ongoing economic growth. Local economies in which people maintain a sense of place and a sense of their ecological and cultural limits provide an alternative, resilient model to the infinite growth paradigm.

—

Claudia Múnera is a conservation biologist and the director of CASSE’s Colombia Chapter.

Interesting perspective, thank you. I’ve witnessed some loss of my own biocultural heritage in the State of Missouri – loss of biodiversity and an erosion of sense of place.

Claudia,

I enjoyed your article and agree with your conclusions.

When it said: ” According to the International Institute for Environment and Development, some 370 million indigenous people in the world depend directly on natural resources — ” the thought occurred that all 7 billion people on the ‘Only One Earth’ depend on natural resources; the global endowment; humanities heritage.

Overby.

Hi Claudia,

Very nice and instructive article. Thanks.

Christopher.

The bio-cultural heritage of the Washington, DC – USA – metro area has certainly gone to heck in a handbasket in the last 50 years. A catastrophic of growth of people, hideous commercial architecture and continual tear-down of trees has transformed it into a mess. Rolling back global population is key to getting sanity and wholesome back into the world eco-system. Curbing the greed of business and political hucksters would help enormously as well.